Which First is First?: The Eternal Mysteries (and Potential Pitfalls) of Non-Sport “Rookie” Collecting. By: Darth Bryzzo (Chad A.)

First is all that matters. So say the royal and ancient laws of heredity, land title recording rules, Ricky Bobby’s dad, and a heck of a lot of sports card collectors since at least the dawn of the Beckett Age.

For the better part of a half century now, the “rookie card” has been the true superpower in the Hobby, often relegating the other cards in a player’s career to sniveling vassal status (unless your name is ‘52 Topps Mantle, or a rarified handful of others). Given the intractable extent to which RC mania is now hard-wired into the sports card collecting psyche, it’s unsurprising that the concept would migrate to nonsport card collecting as well.

Although nonsport cards have been produced as long as—or longer than— most types of sports cards, and although nonsport collecting has seemingly gained traction in recent years, that expansive area of the broader trading card Hobby is still relatively virgin forest in many respects compared to the industrialized grandeur of sports cards. As participation in the nonsport area of the Hobby proliferates, an increasing (or at least increasingly visible and vocal) cadre of collectors and dealers seem to be singularly focused on “rookie” cards.

There are some important practical differences between sports card and nonsport card collecting, however, that create potential peril for the unwary who blithely apply the “rookie” card concept to nonsport. The purpose of this article is to identify and discuss some of the critical factors potential nonsport card collectors may want to consider before spending significant money on alleged “rookie” cards.

While I am not personally a big fan of trying to graft the “rookie” concept onto nonsport cards, I understand that the Hobby is going to do it regardless of what I think, and trying to alter that would be utterly quixotic. Consequently, my objective here is not to try to steer folks away from nonsport “rookie” collecting, if that’s what they really want to do.

Instead, I would like folks who go that route—especially those newer to the nonsport collecting space—to understand some of the potential challenges and risks that can inhere in identifying and purchasing nonsport “rookie” cards at the present time, when there remain so many uncertainties about the total universe of existing cards and there is a relative absence of Hobby-wide agreement on several critical classification/definitional issues (including exactly what constitutes a “card” in the first place).

The Classification Quandaries

Many collectors in both the sports and nonsport areas of the Hobby today would be inclined to say that a “rookie” card is more or less a traditional trading card (in terms of size and composition) that was issued in North America and was pulled out of some sort of retail pack or product.

While exceptions certainly abound in all collecting contexts, that definition works very well for many sports cards, and even for some mainstream nonsport sets produced by major card companies in the last few decades. However, such tight and tidy definitions tend to break down quickly when applied more expansively to nonsport cards throughout history. Indeed, a wide array of factors can add challenging nuance to the identification of potential “rookie” cards in the nonsport arena.

- A “Card” By Many Other Names…

The precise contours of what is a “card” in the nonsport space are not nearly as straightforward as many would casually assume. This uncertainty can complicate (if not inhibit) Hobby market consensus as to “rookie” card status.

Of course, nonsport cards certainly might be rectangular or squarish slabs of cardboard (of varying thickness), even if they might be sized anywhere between a large postage stamp and a jumbo postcard. But even if made of cardboard, they might also come in the circular form of discs or even more exotic geometric shapes (like the trapezoidal cards mixed in with discs and more traditional rectangles in 1972 Monty Gum “Pop Stars”).

In many other instances, however, nonsport “cards” are really some type of sticker. This is especially true in the music sphere (though it can also be the case in many other areas of nonsport, especially vintage releases).

Such stickers might conform to what most would probably expect of a sticker—an image printed on glossy thin paper with some sort of peelable back that, when removed, reveals a self-adhesive sticky surface. It’s equally likely, however, that the nonsport stickers lack self-adhesive backs—and may even have printed backs containing text and/or other graphics (like typical trading cards). Sometimes they may even be made of fairly heavy-stock cardboard (like typical trading cards). In the absence of peelable, self-adhesive backs, it may not be clear that something is really a sticker without reference to a companion album into which the manufacturer intended it (and others in the set) to be manually glued.

While widespread recognition and acceptance of stickers of various types is fairly typical in certain sports like soccer and tennis, the same is not true with respect to the core American team sports. As a matter of practical necessity, however, stickers must generally be considered “cards” for purposes of nonsport collecting, lest many historically-notable celebrities be rendered tragically cardless. Indeed, if stickers don’t count as cards, then many of the greatest bands and other musical performers (not to mention quite a few timeless actors/actresses and iconic fictional characters) of the last half of the 20th Century have little or nothing to collect, at least from their lifetimes and/or respective heydays.

- Pack Pulled vs. Snack Pulled (or Hand Cut or Game Played, etc.)

Mode of distribution may also impact whether some collectors consider something to be a bona fide “rookie” card.

While some nonsport cards and stickers—even decidedly vintage ones—were indeed issued in some sort of sealed packs (though rarely made of waxy paper), such distribution can’t be said to have been the norm. Many important nonsport cards of globally-iconic cultural figures were issued by other means.

Some stickers were packaged only as sets and issued with the albums intended to house them. Some cards and stickers were premium pack-ins with a wide variety of confectionary or other food products. Some were inserts or cut-outs from various print periodicals or were mailaway promotions or other types of giveaways. Yet others might have been issued as components of various card or board games.

In sports cards, it doesn’t usually create huge problems to just say that a card has to be “pack pulled” to be a true “rookie” card, as the vast majority of the most popular athletes will have some qualifying card (and these days, hundreds or thousands of them). But in the nonsport arena, a sweeping disregard of everything that didn’t come from a sealed retail pack could—once again—cause a good many important celebrities and historical figures to have no recognized cards at all.

- Spanning the Globe—the Wide World of Nonsport.

With many aspects of mainstream sports card collecting, it’s easy (and safe) to assume that most of the key cards originated from the United States or Canada. Nothing could be further from the case when it comes to nonsport cards.

True enough, a good number of ultra-modern celebrities have North American cards from products like Topps Allen & Ginter, Upper Deck Goodwin Champions, and Leaf Pop Century. Moreover, some “vintage” celebrities also have domestically-produced cards. But the lion’s share of the cards for many of the most iconic pop culture figures of all time hail from a truly global range of countries on continents other than North America.

Many key cards from the early decades of the 20th Century were tobacco cards and/or game cards produced in the UK. Other noteworthy sets were confectionary tie-ins from places like France, Italy, Germany, Belgium, and Spain.

Approaching mid-century, more cards and stickers were also being issued in places like Portugal, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Finland, often (though not exclusively) as inclusions with chocolates, other candies, pastries, or gum. There are also some appealing South American issues from this timeframe.

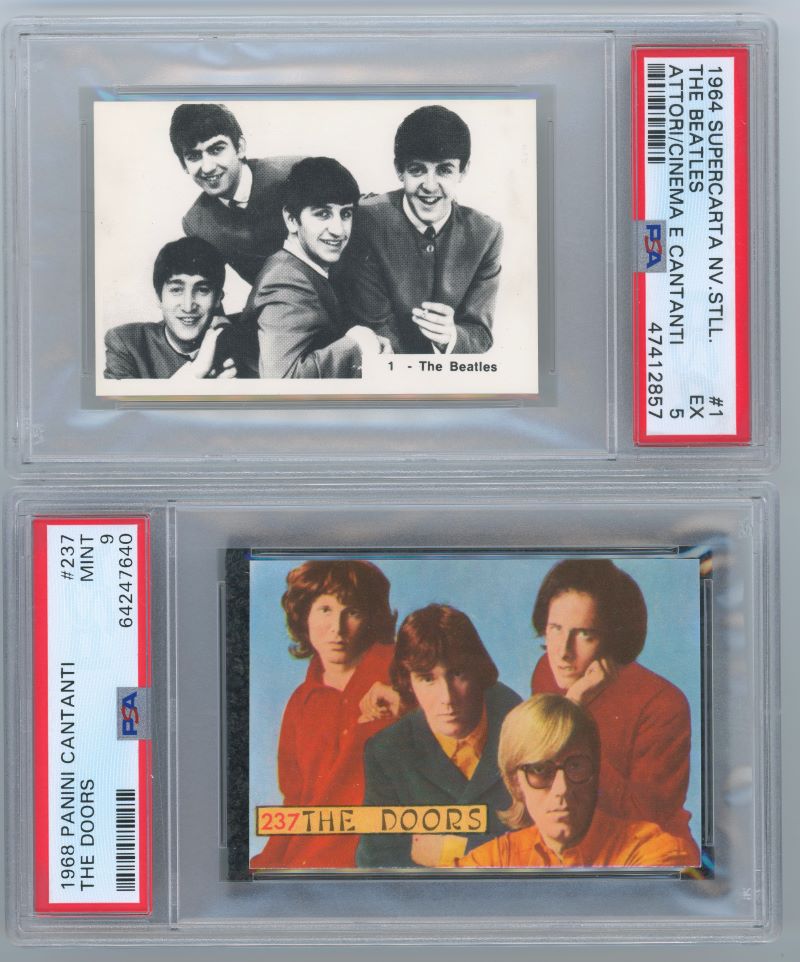

Production from many of those places continued (if not increased) into the ‘60s and ‘70s. The Panini stickers that began to emerge from Italy in the late ‘60s would be central pillars of the music cardscape for the rest of the 20th Century and into the 21st. Various sets from the Netherlands, Sweden, Germany, and Spain during the ‘70s are also very important, especially in the music space.

In the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s, while companies like Topps, O-Pee-Chee, and Donruss expanded upon some of their earlier television and film issues, sets from the Netherlands, Spain, UK, Australia and various parts of South America were also very important, and contain cards for many noteworthy actors/actresses, shows, films and bands/singers not featured in any of the more familiar North American sets. Additionally, even some of the most famous North American entertainment sets—such as 1977 Topps Star Wars—have analogue sets issued elsewhere around the globe, including Argentina, Mexico, the UK, France, Italy, Australia, and New Zealand.

Refusing to acknowledge and consider the century-plus worth of cards and stickers that have originated (and continue to originate) from beyond North America is not only unduly dismissive of the world at large, but again would render many of global pop culture’s most iconic and enduring luminaries effectively cardless—at least in terms of cards issued at or near the time of their greatest career activities and achievements (i.e., the nonsport equivalent of “playing days” cards).

- Subject Matter Identity Conundrums.

Beyond the challenges posed by the protean characteristics of “cards” and the almost boundless variety of places from which they might come, some befuddling identity-related questions may also bear on the “rookie” determination for at least some categories of nonsport cards.

For starters, with respect to actors and actresses, how do we treat their cards as fictional characters versus cards as themselves for purposes of “rookie” classification? (Example: Are 1977 Topps Star Wars Princess Leia cards only character “rookies,” or are they also Carrie Fisher “rookies”?) And once an actor or actress has had a “selfie rookie” of some type, does each different fictional character throughout the remainder of his or her career nonetheless have a separate “character rookie”? (Ex: Are there Indiana Jones “rookies” in 1981 Topps Raiders of the Lost Ark even though Harrison Ford had numerous cards as both Han Solo and himself in the years prior to that release?)

What if an actor/actress or fictional character first appears on a card with others (who may or may not be appearing on a card for the first time)? Is that ensemble card the “rookie” for the particular individual in question, or must that individual instead appear alone on a card for it to count as a “rookie”?

On the flip side, in the music realm, is a band’s only “rookie” the first card featuring members of some historical configuration of the band, or does each major change in band composition create a new “rookie”? And if the latter, how do we know when a lineup change is critical enough to trigger a fresh “rookie” card? (Ex: Is the 1972 Panini Cantanti Pink Floyd card featuring the band’s classic lineup from the ‘70s a “rookie” even though the band without key member David Gilmour had at least three pieces prior to that in the 1969-71 German Bergmann sets?)

Beyond vagaries of who is in a band when, what if the first card bearing a band’s name pictures just part of the band’s lineup, such as a lead singer or lead guitarist or some less-than-complete combination of its members? Do such “partial headcount cards” count as band “rookies,” or must all band members at the time of card issuance be depicted for it to count as a band “rookie”? (Ex: Can the 1978 Swedish Samlarsaker gum card that says “Van Halen” but features only lead singer David Lee Roth be the band’s “rookie”?) If the latter, do you then make a special allowance (in retrospect) for a partial group card if the band never ends up having a card that depicts all of its members?

What about someone who becomes most known as a solo performer, but who started out as part of a band or other group? (Examples are legion: Michael Jackson, Rod Stewart, Beyonce, Justin Timberlake, etc.) Is that person’s only “rookie” the first card on which he/she appears, no matter the context, or can he/she have both a band/group “rookie” and a later solo career “rookie”?

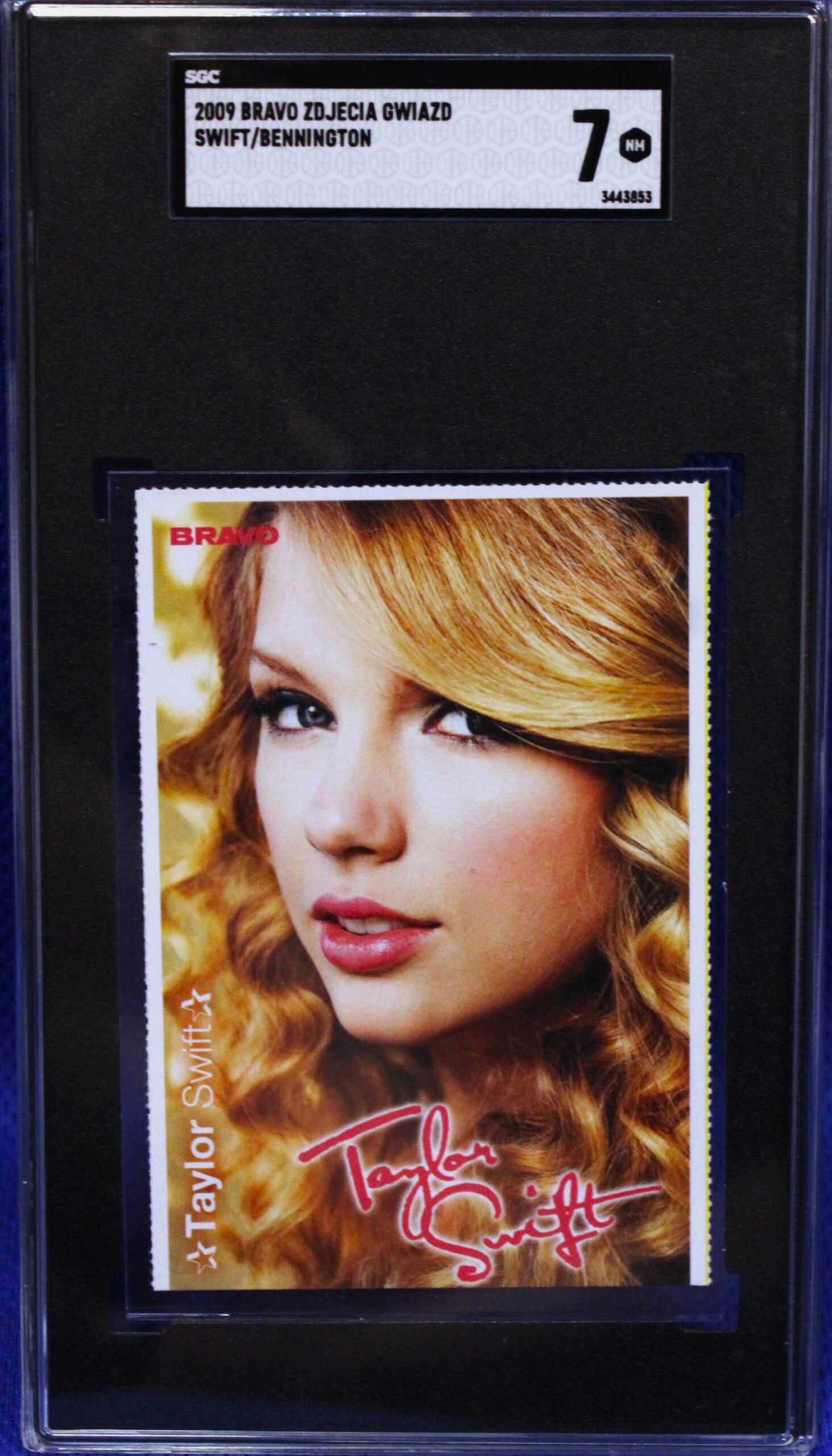

Conversely, what if a solo artist first appears on a card with someone else? Is that multi-person card the solo performer’s “rookie,” or is the “rookie” instead the first card on which he/she appears alone? Or are they both somehow different types of “rookies”? (A good example of this would be the 2011 Topps American Pie card featuring Taylor Swift and her ultra-nemesis, Kanye West—if that was actually Taylor Swift’s first card, which is not the case, even though huge swaths of the market think that it is.)

While the whole “rookie” card concept may seem so lullingly simple and alluring in the abstract, as applied to many categories of nonsport cards, it can get really maddening really quickly.

- The Fateful Vagaries of Set Construction & Numbering.

Identity questions are not the last quandaries when it comes to nonsport “rookies.”

In at least modern and ultra-modern sports cards, most of a player’s first-year cards will bear the “RC” symbol. True enough, the market will often decide that some rookie cards are more important (and valuable) than others, but all first-year cards are today generally classified as some type of rookie card.

In at least some areas of nonsport, however, some Hobby participants advocate for a much narrower conception of the “rookie.” This seems to arise quite a bit with respect to television and movie sets, where only a character spotlight card and/or the first sequentially-numbered card of a given character within a given set will be deemed the “rookie,” rather than all cards in the first-year set(s) featuring that character. (Ex: In 1977 Topps Star Wars, some consider Luke Skywalker #1 and Han Solo #4 to be the ONLY “rookie” cards for those iconic characters, even though the same first series—let alone the broader 1977 set—contains many other great cards of those characters.)

Whether you like or agree with this convention or not, it’s definitely a thing, at least in some pockets of nonsport, and if you are dead set on collecting nonsport “rookies,” you need to be aware of it, as it can create significant cost/value impacts for certain cards.

For numerous modern television and film sets, one must also account for promotional cards (which might be anything from pack-pulled special inserts in other sets to limited giveaways at major conventions, such as ComiCon). If you don’t consider promo cards to be “rookies,” then I guess my first question would be: When is first first, and when (and why) is first not first? And then I guess my next question would be: What are promo cards then, some sort of entertainment industry XRC? (Do we really want to go down that side alley again?)

- The Dating Experience Gets an Incomplete Grade.

Efforts to determine true first cards for nonsport subjects are also sometimes complicated by imprecisions in the card grading process. There are a number of significant nonsport sets that ran over the course of numerous years, with the overall runs sometimes straddling parts of different decades. Illustrative examples include Victoria Vedetten Parade from Belgium (mid ‘60s to early ‘70s) and Samlarsaker from Sweden (mid ‘70s to early ‘80s).

When grading examples from such multiyear sets, at least some of the grading companies seem inclined to take a single year from the overall production run and assign it to all cards in the set, instead of determining in exactly which year within the broader run each particular card was issued. For example, many cards in the Swedish Samlarsaker set are identified as having been issued in 1978, even though they might have been issued anywhere from roughly 1974-81.

This sort of dating imprecision can sometimes lead to comically absurd results, with some very notable celebrities—including Frank Sinatra and Elvis—having certain graded cards floating around out there bearing dates that are years before their careers actually began.

Amusing or not, it can certainly be very confusing to many Hobby market participants, and helps to thicken the fog that often permeates the nonsport “rookie” landscape.

Inherently Risky Business

Before committing substantial sums to purchase alleged nonsport “rookie” cards, collectors would be wise to carefully evaluate the extent to which the Hobby market seemingly has or hasn’t yet reached workable consensus regarding the foregoing types of key classification issues. And even if the market has done so for a given card, one should understand the risk that today’s consensus might not be eternal, allowing for value-altering shifts in market sentiments and preferences over time.

One should also appreciate the equal—if not superseding—risk that something else could very well surface in the future to upend the Hobby market’s current understanding of what is really a given cultural figure’s first card.

The Uncharted (Unchartable?) Universe

Even if the numerous thorny categorical quandaries don’t derail the “rookie” collecting impulse in nonsport, unavoidable uncertainty as to what exactly is out there for most nonport subjects poses significant additional challenges and risks.

Compared to the sports card arena, there is a real resource deficit when it comes to being able to readily identify what all is out there for a given actress, director, fictional character, singer, band, etc. The uncertainty is exacerbated mightily by the number of items that can be considered nonsport “cards” and the sheer number of places from which they might originate.

Online resources like Trading Card Database, COMC (including “sold out” items in searches), and even super-collector sites like www.moviecard.com may all be very directionally helpful jumping-off points. All have gaps, however, and must often be augmented by communication and collaboration with experienced collectors and dealers (some of whom hopefully have access to albums issued with certain sets, which serve as de facto checklists).

Even then, very experienced collectors and dealers are also prone to blind spots, as the total expanse of nonsport is so vast that no one person (or even small group of people) can effectively master it all in a collecting lifetime.

A few illustrative examples (out of many possibilities):

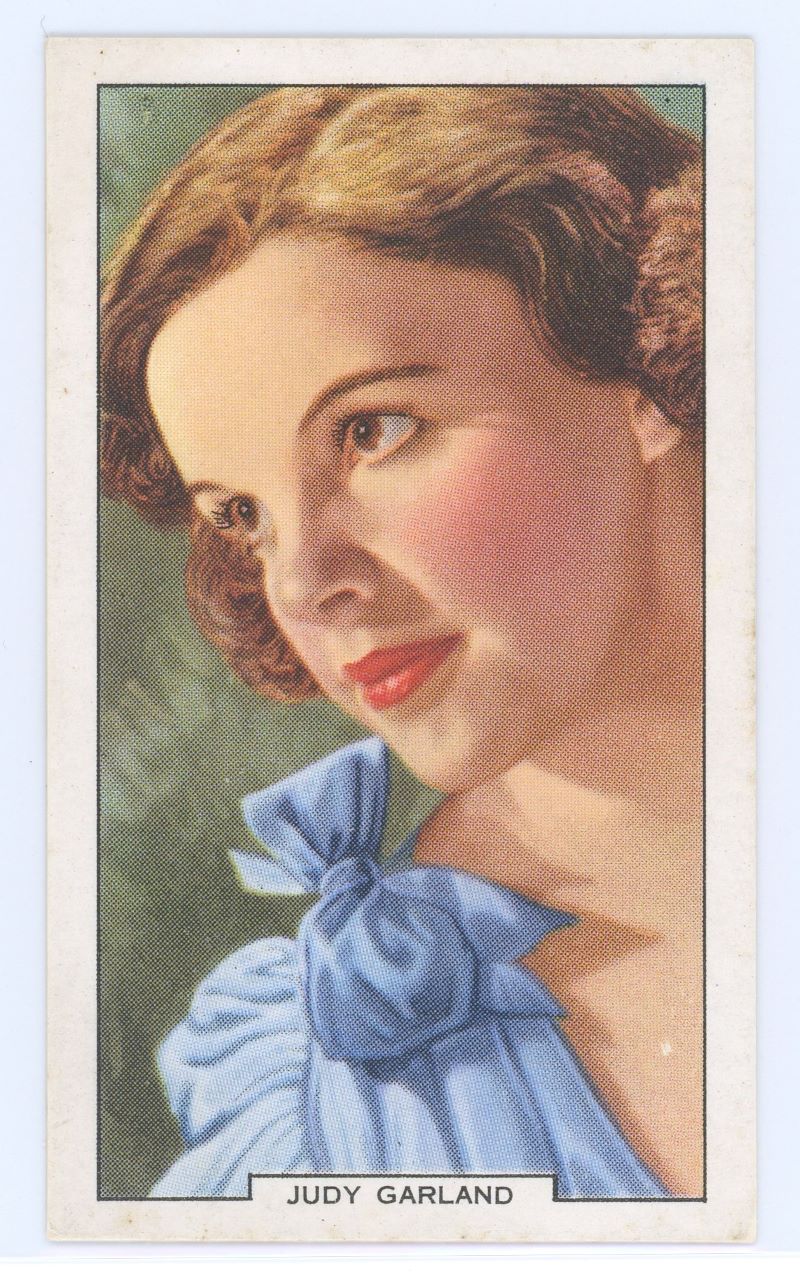

- Many collectors consider Judy Garland’s “rookie” to be a 1939 Gallaher “My Favourite Part” tobacco card from the UK. However, about a year ago, I became aware of at least two—and possibly three—very scarce cards of her from other European countries that are at least from 1939, and more likely from 1938.

- Most market participants consider Madonna’s “rookie” to be a 1985 Panini (Italy) “Smash Hits” sticker. However, Madonna also has a number of other key pieces from 1985, including a far more scarce sticker from Panini’s Tutto set. Most critically, she also has an uber-scarce “Rock Blocks” card from 1984 that was issued exclusively by the Coles grocery store chain in Australia.

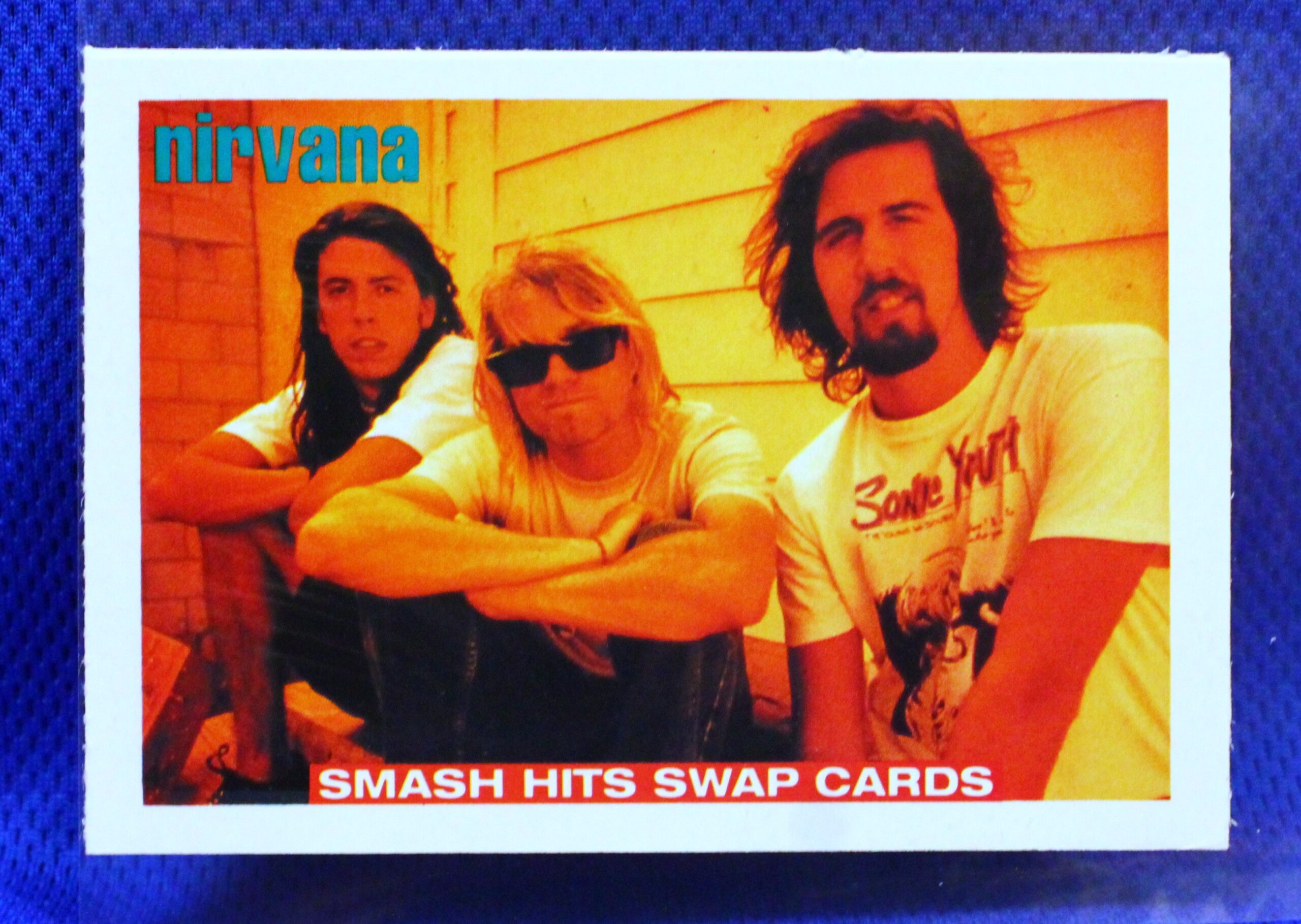

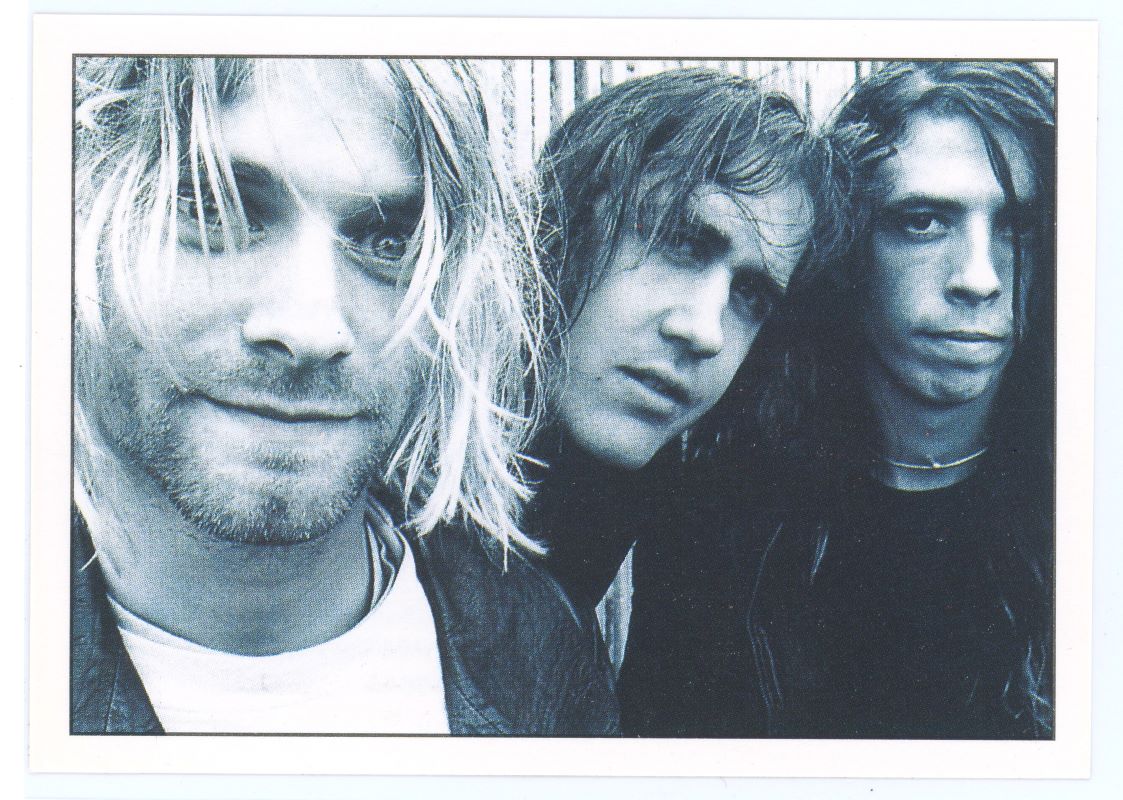

- Many folks in the market claim Nirvana’s “rookie” is from 1995 Panini “Smash Hits.” Others claim it is from a 1994 South American set often called “Ultra Figus.” And yet, Nirvana (and Kurt Cobain individually) have scarce pieces from various worldwide sets dating back to at least 1992—and possibly even earlier.

If things are not settled and generally agreed upon for stars of this magnitude—including someone like Judy Garland, who has been a global star for 85+ years—how much certainty and predictability can collectors in this space ever really expect?

To use a mangled science-y analogy, such examples underscore that the universe of nonsport cards is filled with “dark matter” and invariably governed by an underlying “uncertainty principle,” for which there may never be a full and permanent solution.

Misusing, Abusing & Confusing: The Ubiquity of the “Rookie” Label in the Nonsport Marketplace.

Some sellers (from ebay to IG) seem to react to all of the inherent uncertainty by calling virtually every nonsport card a “rookie.” In some instances, this may be due to sincere and well-intentioned ignorance (which is understandable). In other instances, the misuse/overuse of “rookie” seems potentially due to laziness. And sometimes, it seems to be knowing and intentional—seemingly calculated to mislead.

Regardless of a given seller’s motives, personal knowledge base, and/or efforts (or lack thereof) to confirm hopes and assumptions through research, an aspiring nonsport “rookie” collector should be very leery about casually accepting anyone else’s labels and assurances. Newer collectors in the space, especially, should avail themselves of all available (even if imperfect) resources—especially more experienced collectors—before paying substantial sums for purported nonsport “rookies.” In other words: “Ask Around Before Buying It Now.”

Finding Pockets of Collecting Bliss Amidst the Chaotic Uncertainty

What is the ultimate lesson to be drawn from all of this? Avoid altogether the roiling stew of ambiguity and uncertainty that is nonsport card collecting?

That is actually the polar opposite of my intent. Because of its sheer temporal breadth, subject matter depth, and global scope, nonsport card collecting can be eminently challenging, engaging, and rewarding for a lifetime. It also offers a potential bridge to friends and family members who like movies, tv, and music, but who may not be interested enough in sports to share in a sports card passion. In my view, it would be a tragic shame to forsake all of that wonderful possibility just because it’s not thoughtlessly easy to identify what someone’s “rookie” card might be.

Instead, the primary point here is to make as informed decisions as possible before you spend your money and to always prioritize buying things you truly love. To be sure, those are great (and admittedly cliché) rules to live by in any area of trading card collecting (and/or any type of collecting in general), but I think they are especially critical in the nonsport card space, because of the extent to which it is presently so unpredictably fluid and developing.

Consequently, if you really, really love and really, really want a nonsport card that the market currently regards as a “rookie,” and you love it enough to pay a “rookie” premium for it, and you will love having it in your collection even if it turns out down the road not to be the true “rookie,” then go for it. Alternatively, if you honestly don’t like a card that much, but want it only because it is then thought to be a “rookie,” buy it if you want (it’s your money); but do so understanding that sometime down the road, it’s very possible that future developments might change the market’s view of the card and the “rookie” value premium you paid might completely evaporate.

Of course, we each have to decide what most appeals to us and what we want to do with our (usually not-unlimited) Hobby funds. Whether you want to focus only on “rookies” or not, to enjoy nonsport collecting of any kind, you do have to be able to embrace (or at least tolerate) a measure of chaotic uncertainty, and relish things like the thrill of frequent discovery that completely upends what you thought you knew.

If you are such a collector, I have no doubt that adding some nonsport collecting to your overall Hobby experience can be a gratifying undertaking for the very long haul. It certainly has been (and continues to be) for me.

Author: Chad A. @darthbryzzo on IG

Author Email: darthbryzzo@gmail.com